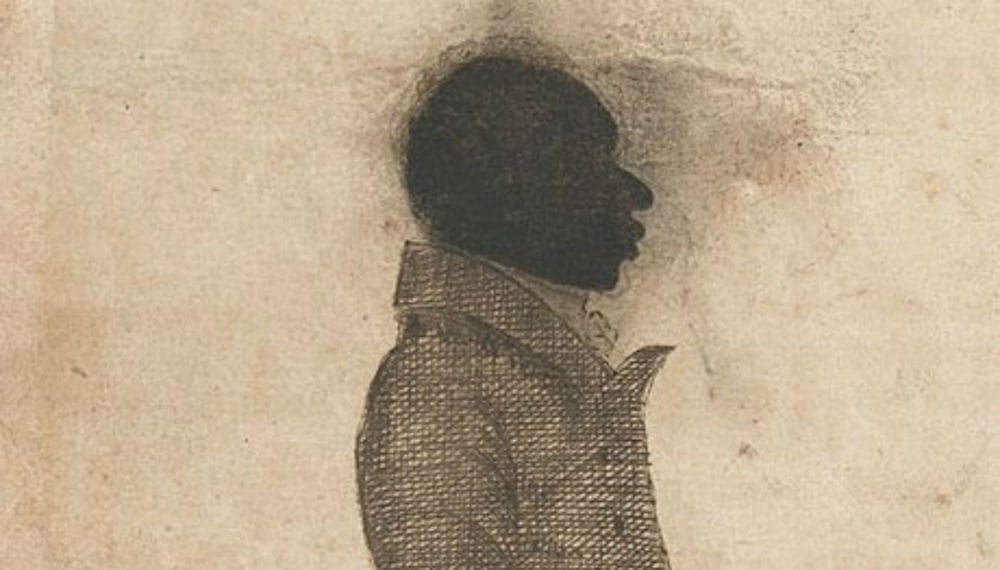

John Jea (1773 – after 1817) was an African-American writer, preacher, abolitionist and sailor, best known for his 1811 autobiography The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher. Jea was enslaved from a young age, and after gaining his freedom in the 1790s, he traveled and preached widely.

John Jea (1773 – after 1817) was an African-American writer, preacher, abolitionist and sailor, best known for his 1811 autobiography The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher. Jea was enslaved from a young age, and after gaining his freedom in the 1790s, he traveled and preached widely.

Early life

Little is known about John Jea’s life apart from what he wrote in his autobiography, The Life, History, and Unparalleled Sufferings of John Jea, the African Preacher (1811).

Jea stated that he was born in Africa in 1773 near Calabar in the Bight of Biafra, and that him and his parents, Hambleton Robert Jea and Margaret Jea, and siblings were kidnapped by slave traders and sold into slavery in New York City when he was two and a half years old. Some historians have expressed doubts over these claims (the likelihood of an entire African family managing to survive capture and the high death rate of the Middle Passage, then to be sold collectively to a single owner, is extremely low), and suggested that they may have been fabricated or embellished.

Jea was purchased and held by a Dutch couple, Oliver and Angelika Triebuen. His masters were members of the conservative Dutch Reform Church, which were against converting enslaved people to Christianity around the time they bought Jea. His master initially sent him to church services as a punishment, but Jea became a devout Christian and was baptised in the 1780s.

Jea was purchased and held by a Dutch couple, Oliver and Angelika Triebuen. His masters were members of the conservative Dutch Reform Church, which were against converting enslaved people to Christianity around the time they bought Jea. His master initially sent him to church services as a punishment, but Jea became a devout Christian and was baptised in the 1780s.

Prior to his conversion, Jea harbored hatred for Christianity. He associated the religion with the violence of his master, for his master views himself as a pious man yet was capable of cruelty, which illustrates the oxymoronic nature of a Christian slave holder. His hatred was so deep that he would rather “[receive] an hundred lashes.”

However, the “salvation rhetoric” chanted by the minister enchanted him and lead to his newfound passion for Christianity.” With greater knowledge on the religion, Jea made his own connections of the hypocrisy of his Christian slave master through finding scriptures that opposes his master’s ideologic thought. For example, his master quoted from the bible “‘Bless the rod, and him that hath appointed it,” as the reason why the enslaved people should thank him for their punishment. In retaliation, Jea quotes the bible within his narrative about how “God is love, and whoso dwelleth in love dwelleth in God” as a query to his master’s cruelty.

During Jea’s teenage years when he had acquired a new passion for Christianity, his master told him that enslaved people have no souls and that he would die “like the beasts that perish,” although he was “treated worse than a beast of burden.” [4][2] However, Jea refuted his master’s claim by referencing the bible his master interpretted for his usage. Alongside renouncing his master’s claims, Jea thanks God for his meals, despite his master’s attempt of proclaiming himself as the one to thank for he tries to convince the enslaved people that he is God. Moreover, Jea declared that he will be guided by none other than God.

Freedom

After passing through a series of slave owners, Jea convinced the final one that his recalcitrance as a slave merited manumission. He was freed by court on the basis of being a faithful, baptised Christian though his enslaver initially refused to heed to the court order. Jea’s faithfulness was backed by his ability to read the first chapter of The Gospel of John, along with the magistrates response of how “no man could read in such a manner, unless he was taught of God.”[7] Jea believed that his conversion equated to his freedom, however “the magistrates only validated his baptism and conversion.”[3] Alongside the fear of Jea teaching other enslaved people about Christianity, came the threat of “[sharing] his newfound literacy with fellow [enslaved people],” giving reason to his emancipation. Through the true reason behind his emancipation, Jea demonstrates how literacy is a key component to freedom.

Later life and travels

Jea tried persuading his family to seek freedom much like how he sought his. However, he was unable to successfully accomplish this task and instead gave ministries to an enslaved person and recounted his tale of Christianity to freedom, which resulted in the enslaved person obtaining his freedom much like Jea. Jea saw this as a sign from God to continue being a minister.

In the 1790s Jea traveled to Boston, New Orleans, New Jersey, South America, and various European countries, where he worked as an itinerant preacher and as a mariner and shipboard cook.[2] During the beginnings as an itinerant preacher, he went from place to place professing the word of God. He did this through an organized manner where him and other preachers made rotations for each week. After three years in Boston, Jea returned to New York to see his mother, siblings, friends. While he was in New York, he had decided to marry a Native American Woman called Elizabeth, who he said had been executed for killing their child. Instead of attributing these murders to the authoritarian pressures inflicted on Elizabeth by her boss because of her husbands “intense piety,” Jea sees “temptation and sin” as the root cause.

Between 1801 and 1805 he lived and preached in Liverpool, England. Jea made use of a methodist style of preaching during his itinerancy. However, Jea was wary of including antislavery sentiments for fear of the violence that might be invoked from pro-slavery lobbyists. He then worked as a cook on ships traveling around North America, the East and West Indies, South America, and Ireland. Although he worked for financial means, he also used his travels as an opportunity to preach the gospel. In the year 1811, Jea’s travels reached a pause when his ship was captured by French forces. There was an opportunity to leave this imprisoned state by joining the American consul, however, Jea’s “pacifist” nature deterred him. He decided against working on a US warship and preaching the gospel there because it clashes with his Christian ideologies. Jea traveled around northern France for four years before his eventual release at the close of the Napoleonic Wars. From Hodges’ knowledge, Jea failed to compromise to participating in the war, which he describes as sinful, and returns to England where he settled in Portsea.

During his stay, Jea published his autobiography and hymnbook during the 1810s. Jea marries his fourth wife Jemima Davis and had a child named Hephazabah, who was later baptized in an Anglican chapel. He was still traveling as late as October 1817, when he was preaching in St. Helier in Jersey where he died.

Jea married Charity, a Maltese woman who died; and Mary, an Irishwoman, who also died, before he married Jemima Davis.

Published works

Jea was one of the first African-American poets to have written an autobiography.[16] His autobiography was written in Portsea between 1815 and 1816, but was largely unknown until it was rediscovered in 1983.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. has argued that Jea’s autobiography forms a “missing link” between 18th-century slave narratives, which tended to focus on spiritual redemption, and later 19th-century narratives, which rhetorically championed the political cause of abolition.[17] Religious themes dominate Jea’s autobiography. Indeed, Jea describes his acquisition of literacy as the result of a miraculous visit from an angel, who teaches him to read the Gospel of John. But political themes are mixed together with these religious aspects, and the work consistently argues that slavery is a fundamental injustice in need of abolition. Gates calls Jea’s work “the last of the great black ‘sacred’ slave autobiographies.”

Jea’s narrative draws upon Biblical allusions and aligns with Henry Louis Gates’ “talking book” trope, which appeared in many early slave narratives. This is the trope where the formerly enslaved person would be able to hear God’s words originating from the Bible, as if the book was talking to them. However, this trope faced a decline as a more “secular context” began to be encourage to establish the narratives’ credibility.

Jea also published a hymnbook called A Collection of Hymns. Compiled and Selected by John Jea, African Preacher of the Gospel (1816). It contains 334 songs, including 29 apparently of Jea’s own composition.

Throughout his narratives and hymns, Jea made allusions to Lazarus

After Jea’s conversion, his narrative shifts from a view of his everday life to a compilation of “mini-sermons” that he connects with himself, and calls this new semantic/syntax Canaan.