(RNS) For novelist Okey Ndibe, Christmas comes down to a few grains of rice.

Ndibe, who is 56, is a “Biafra baby” — a childhood survivor of a terrible civil war that scourged his native Nigeria from 1967 to 1970 and left him and his family homeless and often hungry.

“At each temporary place of refuge, my parents tried to secure a small farmland,” Ndibe wrote in a 2007 essay, “My Biafran Eyes.”

“They sowed yam and cocoyam and also grew a variety of vegetables. We, the children, scrounged around for anything that was edible, relishing foods that in less stressful times would have made us retch.”

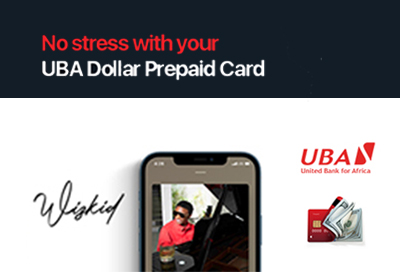

Except on Sundays, when the family would serve a small portion of rice, with each child savoring the few grains he or she received. At Christmas, the family plowed all of its available resources into a single meal of rice and — that rarest of treats — chicken.

A traditional Nigerian Christmas dish of stewed chicken and tomatoes served over rice. Photo courtesy of Okey Ndibe

The taste of that rice and chicken — fried or roasted or stewed with tomatoes — is now Ndibe’s touchstone to Christmases past with family and friends in a Nigeria he left to come to the United States in 1988.

“This was magical,” Ndibe said.

This year, he plans to cook the American version of the meal for his wife, three children and the cousins they will visit in Atlanta from their home in Connecticut.

“Those of us who didn’t have enough to eat at other times because our parents didn’t have the resources looked forward to Christmas and Easter and other religious festivals because those were the occasions every family cooked more than they usually could.”

Chicken and rice are so inseparable from Christmas for Ndibe that, in 1997, when he and his wife had Christmas dinner at the home of some American friends, it never occurred to him they would serve anything else.

“The absence of rice and chicken spelled doom for me,” Ndibe writes in “Never Look an American in the Eye,” his third book and first memoir. “Once it dawned on me that the cuisines I most looked forward to were not about to materialize, I had the equivalent of a culture shock followed by a mild to serious panic attack.”

So he took matters into his own hands, made his excuses to his hosts and took his wife home. It was, of course, too late to prepare a chicken, so he grabbed a scant half cup of rice and put it on to boil.

These days, Ndibe has lived in the U.S. longer than he lived in Nigeria. He has written two critically acclaimed novels and taught at universities from Las Vegas to Lagos. He is the founding editor of African Commentary magazine, which was started by the late Booker Prize-winning novelist Chinua Achebe, who was also Nigerian.

As Ndibe has matured, his concerns have shifted to the more spiritual at Christmas. In Nigeria, he was raised a Catholic — about half of all Nigerians are Christian, concentrated mainly in the south. He still practices his faith and focuses on Advent — the four weeks before Christmas — as a time of spiritual renewal.

In Nigeria, Christmas is the time of what Ndibe calls “the return” — an annual pilgrimage from cities and towns to one’s ancestral village or hometown. Once there, people go from house to house on Christmas and afterward, visiting and eating with family and friends.

Right after Christmas, Ndibe and his four brothers and sisters will travel from their scattered homes in Africa and abroad to see their 92-year-old mother in the Nigerian countryside.

There they will engage in another Nigerian Christmas custom: the passing on of family history and lore.

“Before our Christmas meal at home, my parents would tell us the stories of their lives, their struggles and the narratives of their own parents and how they transcended their difficulties,” he said. “So I do the same thing with my children now. Christmas becomes an occasion to share our dreams, our stories, our obstacles and our ultimate triumph.”

There is one more Nigerian Christmas custom Ndibe maintains. Because the Nigerian version of the holiday doesn’t include gifts beyond a new set of clothes for each family member to wear at Christmas services, he has given up giving and receiving gifts.

“I have as happy a Christmas as anybody, yet I have not received a gift,” he said. “I try to get the kids to see beyond the value of the gift and see they can have a genuine happiness that relies on living the message of Christ without the entrapment of materialism.”

Courtesy: RNS