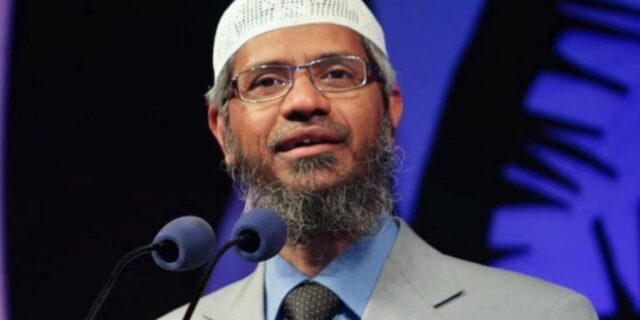

Media accounts of the just concluded visit to Nigeria by the controversial Indian Islamic televangelist, Mr Zakir Abdulkareem Naik, suggest nothing but an apocalyptic scenario, in which a flaming terrorist was given an expanded platform in Sokoto, Abuja, Keffi and Ilorin to plant the seeds of discontent that ultimately bodes the Nigerian political environment nothing but impending chaos, turmoil, and bloodbath in the very near future.

The context for this media anxiety is easy to predict, even if it is unacceptable in its broad myopia and essentialist framework, an outlook which tends to equalise all conservative traditions of Islam as extremism or even terroristic.

At a mental level, Nigerians were coming from a background of two decades of insurgency in the Nigerian North-East, vestiges of inter-religious tension in the land, and lingering issues of faith around the last general elections. These developments in themselves were enough to trigger discomfort with the invitation of a cleric who has a history of controversy.

In his home country, India, and in neighbouring Bangladesh, Zakir Naik is blamed for stoking terror. Bangladesh puts the death of 22 nationals from the July 2016 Holey Artisan Cafe Bombing in Dhaka on him, claiming that one of the bombers was radicalised by him. Naik rejects these accusations.

On its part, India has gone a little further to place bans on his messages and his Islamic Research Centre, ultimately forcing him into exile. Accusing him of spreading hate speech, Narendra Modi’s government also wants to press charges against him for acquiring $28 million worth of ostensibly criminal assets, a claim Naik denies. For these reasons, India has been struggling with Malaysia, Naik’s new home, to extradite him to face charges. His Peace TV is also banned in India, Bangladesh, Canada, Sri Lanka, and the United Kingdom.

As such, this is not just a case about Naik’s credentials. No one is challenging his famous eidetic memory or his knowledge of the text. At any rate, a laureate of the coveted King Faisal International Prize for “service to Islam” deserves attention.

Disturbingly, Naik seemed ready for some controversy at his point of arrival in the country, taking copious pictures for his social media operations, which he classifies thematically as “interactions.” Airport photographs of service men would come, in Naik’s world, as “Interactions with Muslim Air Force” or “Interactions with Muslim Immigration Officers.” In a particularly comic but deeply concerning instance, he strained his game by posting a picture with the Sultan of Sokoto, His Eminence Muhammadu Saad Abubakar, under the caption “Interaction with Heads of State,” prompting a reader to force a correction saying, “the Sultan is not a Head of State.”

Should this be a matter to worry about? Media critics at least have been engrossed in this, probably because Naik’s 16 million Facebook war chest in followers, 1.3 million on Instagram, about 150,000 on X (formerly Twitter), and a cable TV reach of over 200 million people, make him someone in the league of a global media aristocracy. Typically, such powerful people are expected to exercise caution, care, and sensitivity, especially when proselytising in communities constantly on the edge of incendiary passion.

Sultan Abubakar, responding to critics of Naik’s visit at the closing ceremony of the Sheikh Usmanu bin Fordiyo week said, “Muslims have the right to invite their fellow brother for interaction… (and) we are working for Islam, not for everybody.” The monarch added that “as Muslims, we have the right to invite fellow Muslims to interact with us.”

A democratic Nigeria that adequately cherishes civic rights will have no difficulty with the pronouncements of the Sultan. Sadly, there have been many instances in our recent history where proselytising clerics had set off disturbances that led to fatalities and the wanton loss of properties. Consequently, it is important to recognise that Nigeria is still struggling to find a healthy balance with how to manage issues of peace, security, and stability, upon which a sense of community harmony and development can be constructed. We certainly have to carefully manage the potential of all forms of religious proselytisation to foment mayhem in the country. That is one of the main lessons of our recent history.